A huge floor graphic in the HDKV hall marks the beginning of Simon Denny’s ‘Merge’. It shows the surface of the classic Australian board game Squatter, its placement reminiscent of the experience-oriented exhibition design of technology museums. While Monopoly players can imagine themselves as real estate tycoons, Squatter turns them into sheep farmers competing for grazing land, flock size, and wool sales. The game not only reflects the history of settlement in Australia and New Zealand, but also references an archetypal form of extractivism still closely associated with physical labour.

On this both aesthetically and thematically crucial backdrop, Denny distributes a series of large-scale sculptures constructed from sturdy honeycomb cardboard. The pieces are based on representations of modern semi-or fully automated machines and technologies from the spheres of mining, geodata capture and productivity management. The rock-breaking hydraulic hammer from Transmin, the geodata-collecting satellite from US giant DigitalGlobe, the drilling rig simulator from market leader Epiroc, and a biometric smart-band to monitor workplace fatigue all appear on the colourful Squatter board like a strange techno theme park. Denny had the machines’ original industrial look translated into a dystopian gaming aesthetic by game designer Paul Riebe.

This is fitting, on the one hand, because some of the apparatuses depicted are in reality high-tech robots filled to the brim with digital smart power, to be operated by workers as though they were computer games. An example is the Epiroc simulator, which is animated as a good-natured Transformer in the accompanying promo video. On the other hand, Denny’s approach is obvious: after careful observation, we begin to ask ourselves to what extent all these machines are not simply big toys, developed by gambling men who imagine the planet as an oversized sandbox. This made evident by the sometimes devastating ecological consequences and the political entanglements that come into play when it comes to granting permits and circumventing inconvenient regulations, as well as the often inhumane practices towards local workforces—especially in the Global South—are defining features of extractivism. This is why Denny also invited the courtroom artist Sharan Gordon to create a series of authentic-looking courtroom drawings to accompany each of the machines, involving the individual corporations behind them, showing real people—CEOs and executives—during fictional accountability trials.

Some of the sculptures also serve to present the board game Extractor, which Denny developed together with Boaz Levin. While Squatter still turns players into well-behaved sheep farmers, in Extractor, they become managers of data-oriented companies, learning to capture and monetise Big Data from online activities or circumvent onerous constraints such as carbon taxes. In this way, the game not only conveys basic mechanisms of digital “surveillance capitalism” (Shoshana Zuboff, 2018), but also shows extractivism as a prevailing principle of current politics: those who ‘pull out’—the extractivist character already becomes clear in this verb—the maximum level of material and immaterial resources from oneself, the others, and the environment, win.

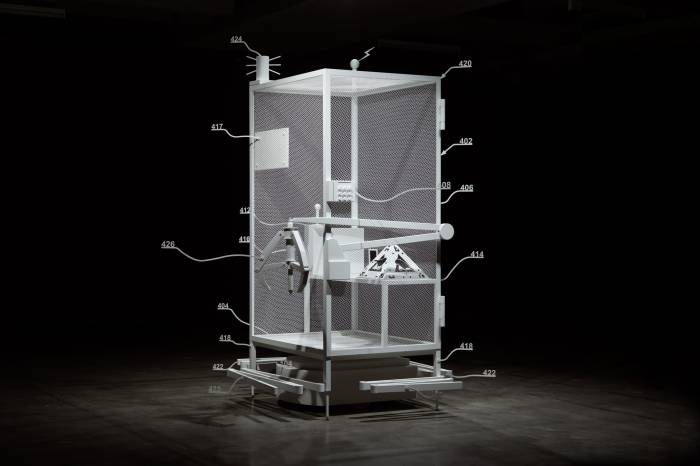

The notion of extractivism as a principle that shapes all kinds of relationships across social spheres is continued on the upper floor of the Kunstverein through the reference to the mining, or ‘extraction’—another linguistic gesture towards extractivism—of cryptocurrencies. The objects in the Centralization vs Decentralization hardware display series are fully functional mining rigs. During the exhibition, they will be actively involved in mining new cryptocurrency. They are simultaneously works of visual art, too. In addition to the relays of graphics cards that were, and still are, used as part of the blockchain infrastructure of a decentralised web, Denny mounts components such as printed board games or Reddit fan art on derelict casing parts formerly used for central mainframe computer systems—infrastructure which represents precisely the order that advocates of decentralised blockchain systems want to disrupt. Collaging components of conventional systems with their antithesis is not an explicitly formal trick, but rather, a reference to disputes that are taking place surrounding the distribution of power on the web. This is about the demand for a democratic internet whose control no longer lies in the hands of a few giants, namely GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon).

The title of the exhibition, ‘Merge’, alludes to the long-awaited and recently realised merge of the Ethereum network with the Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus algorithm. Prior to the merge, Ethereum used Proof-of-Work, the method made popular by Bitcoin, for validating virtual transactions—one which consumes massive amounts of energy. With PoS, it is no longer the computing power of the miners and extra hardware, but the share of coins they hold on the network, that determines their validating power. Thus, ‘the merge’ will drastically reduce energy consumption—some say by up to 99.95%.

Through the way Denny interprets technology, he always raises the essential question of how we want to shape our world and lives.

– Søren Grammel, curator of the exhibition